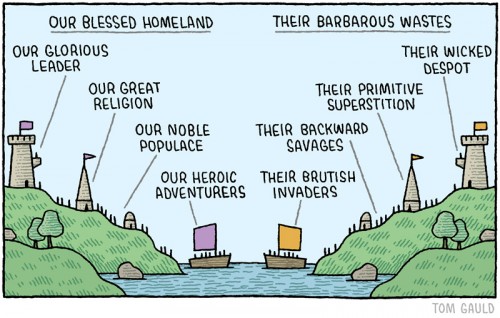

By Tom Gauld.

By Tom Gauld.

(View original at http://thesocietypages.org/socimages)

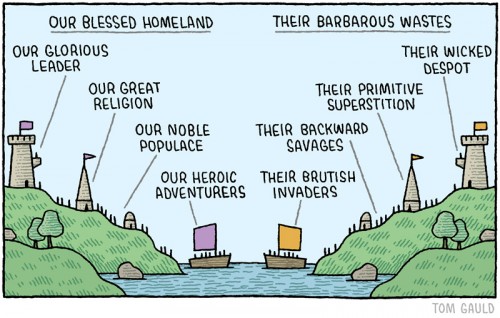

By Tom Gauld.

By Tom Gauld.

(View original at http://thesocietypages.org/socimages)

Every so often, when I am called upon to sign some contract or other, I have a conversation that goes like this:

Me: I can't sign this contract; clause 14(a) gives you the right to chop off my hand.

Them: Oh, the lawyers made us put that in. Don't worry about it; of course we would never exercise that clause.

There is only one response you should make to this line of argument:

Well, my lawyer says I can't agree to that, and since you say that you would never exercise that clause, I'm sure you will have no problem removing it from the contract.

Because if the lawyers made them put in there, that is for a reason. And there is only one possible reason, which is that the lawyers do, in fact, envision that they might one day exercise that clause and chop off your hand.

The other party may proceed further with the same argument: “Look, I have been in this business twenty years, and I swear to you that we have never chopped off anyone's hand.” You must remember the one response, and repeat it:

Great! Since you say that you have never chopped off anyone's hand, then you will have no problem removing that clause from the contract.

You must repeat this over and over until it works. The other party is lazy. They just want the contract signed. They don't want to deal with their lawyers. They may sincerely believe that they would never chop off anyone's hand. They are just looking for the easiest way forward. You must make them understand that there is no easier way forward than to remove the hand-chopping clause.

They will say “The deadline is looming! If we don't get this contract executed soon it will be TOO LATE!” They are trying to blame you for the blown deadline. You should put the blame back where it belongs:

As I've made quite clear, I can't sign this contract with the hand-chopping clause. If you want to get this executed soon, you must strike out that clause before it is TOO LATE.

And if the other party would prefer to walk away from the deal rather than abandon their hand-chopping rights, what does that tell you about the value they put on the hand-chopping clause? They claim that they don't care about it and they have never exercised it, but they would prefer to give up on the whole project, rather than abandon hand-chopping? That is a situation that is well worth walking away from, and you can congratulate yourself on your clean escape.

[ Addendum: Steve Bogart asked asks on Twitter for examples of unacceptable

contract demands; dealbreaker

clauses. Some I thought of so many that I put them in a separate

article. ] immediately include: Any nonspecific

non-disclosure agreement with a horizon more than three years off,

because after three years you are not going to remember what it was

that you were not supposed to disclose. Any contract in which you

give up your right to sue the other party if they were to cheat you.

Most contracts in which you permanently relinquish your right to

disparage or publicly criticize the other party. Any contract that

leaves you on the hook for the other party's losses if the project is

unsuccessful. ]

In December, Google's Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt was interviewed at the CATO Institute Surveillance Conference. One of the things he said, after talking about some of the security measures his company has put in place post-Snowden, was: "If you have important information, the safest place to keep it is in Google. And I can assure you that the safest place to not keep it is anywhere else."

The surprised me, because Google collects all of your information to show you more targeted advertising. Surveillance is the business model of the Internet, and Google is one of the most successful companies at that. To claim that Google protects your privacy better than anyone else is to profoundly misunderstand why Google stores your data for free in the first place.

I was reminded of this last week when I appeared on Glenn Beck's show along with cryptography pioneer Whitfield Diffie. Diffie said:

You can't have privacy without security, and I think we have glaring failures in computer security in problems that we've been working on for 40 years. You really should not live in fear of opening an attachment to a message. It ought to be confined; your computer ought to be able to handle it. And the fact that we have persisted for decades without solving these problems is partly because they're very difficult, but partly because there are lots of people who want you to be secure against everyone but them. And that includes all of the major computer manufacturers who, roughly speaking, want to manage your computer for you. The trouble is, I'm not sure of any practical alternative.

That neatly explains Google. Eric Schmidt does want your data to be secure. He wants Google to be the safest place for your data as long as you don't mind the fact that Google has access to your data. Facebook wants the same thing: to protect your data from everyone except Facebook. Hardware companies are no different. Last week, we learned that Lenovo computers shipped with a piece of adware called Superfish that broke users' security to spy on them for advertising purposes.

Governments are no different. The FBI wants people to have strong encryption, but it wants backdoor access so it can get at your data. UK Prime Minister David Cameron wants you to have good security, just as long as it's not so strong as to keep the UK government out. And, of course, the NSA spends a lot of money ensuring that there's no security it can't break.

Corporations want access to your data for profit; governments want it for security purposes, be they benevolent or malevolent. But Diffie makes an even stronger point: we give lots of companies access to our data because it makes our lives easier.

I wrote about this in my latest book, Data and Goliath:

Convenience is the other reason we willingly give highly personal data to corporate interests, and put up with becoming objects of their surveillance. As I keep saying, surveillance-based services are useful and valuable. We like it when we can access our address book, calendar, photographs, documents, and everything else on any device we happen to be near. We like services like Siri and Google Now, which work best when they know tons about you. Social networking apps make it easier to hang out with our friends. Cell phone apps like Google Maps, Yelp, Weather, and Uber work better and faster when they know our location. Letting apps like Pocket or Instapaper know what we're reading feels like a small price to pay for getting everything we want to read in one convenient place. We even like it when ads are targeted to exactly what we're interested in. The benefits of surveillance in these and other applications are real, and significant.

Like Diffie, I'm not sure there is any practical alternative. The reason the Internet is a worldwide mass-market phenomenon is that all the technological details are hidden from view. Someone else is taking care of it. We want strong security, but we also want companies to have access to our computers, smart devices, and data. We want someone else to manage our computers and smart phones, organize our e-mail and photos, and help us move data between our various devices.

Those "someones" will necessarily be able to violate our privacy, either by deliberately peeking at our data or by having such lax security that they're vulnerable to national intelligence agencies, cybercriminals, or both. Last week, we learned that the NSA broke into the Dutch company Gemalto and stole the encryption keys for billions yes, billions of cell phones worldwide. That was possible because we consumers don't want to do the work of securely generating those keys and setting up our own security when we get our phones; we want it done automatically by the phone manufacturers. We want our data to be secure, but we want someone to be able to recover it all when we forget our password.

We'll never solve these security problems as long as we're our own worst enemy. That's why I believe that any long-term security solution will not only be technological, but political as well. We need laws that will protect our privacy from those who obey the laws, and to punish those who break the laws. We need laws that require those entrusted with our data to protect our data. Yes, we need better security technologies, but we also need laws mandating the use of those technologies.

This essay previously appeared on Forbes.com.

There is a famous story told in Chassidic literature that addresses this very question. The Master teaches the student that God created everything in the world to be appreciated, since everything is here to teach us a lesson.

One clever student asks “What lesson can we learn from atheists? Why did God create them?”

The Master responds “God created atheists to teach us the most important lesson of them all — the lesson of true compassion. You see, when an atheist performs and act of charity, visits someone who is sick, helps someone in need, and cares for the world, he is not doing so because of some religious teaching. He does not believe that god commanded him to perform this act. In fact, he does not believe in God at all, so his acts are based on an inner sense of morality. And look at the kindness he can bestow upon others simply because he feels it to be right.”

“This means,” the Master continued “that when someone reaches out to you for help, you should never say ‘I pray that God will help you.’ Instead for the moment, you should become an atheist, imagine that there is no God who can help, and say ‘I will help you.’”

ETA source: Tales of Hasidim Vol. 2 by Mar

I started reading this and was worried it would be something attacking atheists, or bashing religion, but this makes me really, really happy.

Earlier today, Facebook confirmed it was rolling out a system that labels links from The Onion and others as “satire,” so that your idiot friend from high school would (hopefully) realize that the President didn’t run over Jimmy Carter with his car, or that Dick Van Dyke may not have been the Zodiac killer. Oddly enough, the esteemed news source’s response to the Facebook announcement is much closer to truth than it is to satire.

Earlier today, Facebook confirmed it was rolling out a system that labels links from The Onion and others as “satire,” so that your idiot friend from high school would (hopefully) realize that the President didn’t run over Jimmy Carter with his car, or that Dick Van Dyke may not have been the Zodiac killer. Oddly enough, the esteemed news source’s response to the Facebook announcement is much closer to truth than it is to satire.

“Area Facebook User Incredibly Stupid,” reads the headline.

“I need stuff easy,” explains the area imbecile. “I like looking at things on Facebook, but I don’t understand a lot. Help, please.”

Consumerist reader K points out that the Facebook “satire” tag experiment seems to be working, at least on this story:

Unfortunately, some area fools will see the satire tag and assume that this story does not apply to their lives.